Impacts of environmental pollution upon Indigenous Peoples

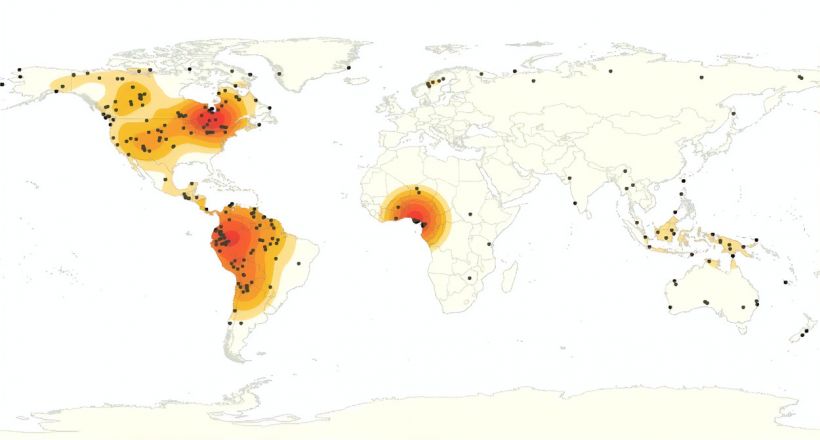

IPs are amongst the populations at highest risk of impact by environmental pollution for two main reasons. First, as IPs’ land- and seascapes tend to be sparsely populated, but rich in resources like ores or oil and gas, they are often the targets of extractive operations that entail pollution risks. And second, IPs are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of pollution due to their high and direct dependency on local natural resources, limited access to health care, and very limited governmental support in their fight against environmental and human-rights injustices. In our new literature review, published in the journal Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, we documented impacts of environmental pollution among 141 different Indigenous groups from all inhabited continents, based on 686 studies published on this topic.

We identified three main types of impacts of pollution on the well-being of IPs i) environmental, ii) health, and iii) cultural impacts. First, IPs inhabit some of the most ecologically undisturbed areas of the world, often of outstanding biodiversity importance. Thus, pollution on their land- and seascapes has an uneven and significant impact on critical environments, affecting large numbers of wildlife species. Our review shows the accumulated evidence for pollution-driven environmental degradation in many land and seascapes inhabited by IPs. Second, most pollution-related health impacts documented among IPs are mediated through the consumption of polluted water and food, including wild foods obtained through hunting, fishing, and gathering. Environmental pollution directly increases IPs risks and burdens of disease. Our review found numerous studies documenting increased risks of diabetes, infections, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, as well as high rates of miscarriage and increased cancer incidence and mortality, including high incidence of childhood leukemias, among IPs living near polluted areas. Impacts of pollution upon IPs mental health, including evidence of neurological and psychological disorders, are also common in the literature. Finally, pollution has affected traditional ways of life and the knowledge systems underpinning them. For example, herbicide treatments by the US Forest Service has contaminated plants used by California Native American tribes for religious, medicinal, or other cultural uses, including traditional basket-weaving where holding reeds in the mouth is part of the weaving process. Because activities associated with collecting country foods (including hunting or bushmeat preparation) generally serve important community roles, concerns associated to pollution regarding the consumption of wild foods can also impact these practices. Finally, pollution can also affect the spiritual wellbeing of Indigenous communities, when natural elements considered sacred (i.e., water) are desecrated through pollution.

How do Indigenous Peoples fight pollution?

A growing body of literature show that IPs are actively contributing to develop innovative strategies to limit or stop ongoing pollution and fighting to prevent it from the outset. Our literature review identified several pathways in which IPs have contributed to prevent, control and limit pollution from local to global scales. First, IP have resisted the establishment of polluting activities upon their territories. Resistance against polluting activities includes actions such as protests and calls for policy action; occupation of resource infrastructures, such as pipelines, power plants and landfills; and litigation to hold polluters to account. Many of these conflicts have resulted in the prevention of the installation of polluting industries upon IPs territories. Second, IP have maintained traditional management systems contributing to pollution buffering and nutrient cycling, with some literature showing that the abandonment of certain Indigenous traditional management practices does often result in increasing levels of pollution. Third, IP are increasingly engaging in programs monitoring the spread and intensity of pollution. While many of these monitoring programs are often conducted by scientists, with IP participation, several Indigenous-led pollution monitoring programs are starting to emerge, based on community-identified needs and priorities. Fourth, IP have participated in the development of policies for pollution control. For example, the Northern Aboriginal Peoples’ Coordinating Committee on POPs led to the Inuit Circumpolar Council participating in the negotiations of the Convention on Long Range Transboundary Air Pollution (CLRTAP) Protocols on POPs and Heavy Metals. Finally, IP facing pollution threats have also been savvy users of legal systems to limit or stop polluting activities in their territories and to obtain compensation or remediation after pollution events. Their claims have often emphasized that their high exposure to pollution is generally due to polluting activities that are imposed on IP lands for the benefit of others, such as resource users elsewhere.

So, what’s next?

The literature reviewed suggests that IPs are largely and heavily affected by polluting activities both through their exposure and vulnerability, but are also playing an active role in limiting and monitoring polluting activities. However, the contributions of IPs to prevent, limit and control pollution have been seldom recognized and the important environmental justice issues surrounding IPs, in that they did not create much of the pollution they are exposed to, remain neglected by both national and international laws.

Based on the evidence reviewed, we suggest that greater engagement of IPs on the governance of resources can help incorporating IPs’ social, spiritual and customary values in environmental quality and ecosystem health; and that IPs should be part of any conversation on policy options to bring pollution down to levels that are not detrimental to human well-being, ecosystem services and biodiversity.

Reference:

Fernández-Llamazares Á, Garteizgoeascoa M, Basu N, Brondizio ES, Cabeza M, Martínez-Alier JM, McElwee P, Reyes-García V (2020) A State-of-the-Art Review of Indigenous Peoples and Environmental Pollution. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. doi: 10.1002/ieam.4239